Victorian Landcare Magazine - Winter 2017, Issue 69

Climate change has become a politically charged topic in Australia, and it seems our voting preference is heavily influenced by our trust in science. But here’s the thing: our plants and animals don’t care about politics, and they don’t lie!

Plants and animals demonstrate the truth by their responses to the conditions to which they are exposed. An increasing body of evidence continues to be gathered from plants and animals that proves climate change is already well underway.

The agricultural sector has been noting these changes for some time. This is the plant and animal story as told by wine grapes, pastures and crops. Their responses to a changing climate are not opinion, just evidence.

Wine grapes have been ripening earlier in Australia in recent years. In 2016 some vineyards harvested up to four weeks early and picking started as early as February. Winemakers are meticulous in their measurement of grape sugar content leading up to harvest, graphing these for each field and vintage to ensure harvest of the best quality grapes for their wine.

Higher spring temperatures mean the grapes respond by ripening earlier, this also results in a more compressed vintage that presents an increasing logistical challenge for processing capacity on the vineyard.

Winemakers visit each vineyard as the season progresses taking samples of the grapes to measure their sugar content, measured as brix. The best pinot noir wine results from a harvest when the grapes measure 23.6 brix. Natural variability of the date when the grapes reach the brix target are to be expected, but between 1984 and 2007 the average maturation date of pinot noir grapes across southern Australia has been advancing by eight days per decade.

Earlier harvests of eight days per decade were also recorded in Colmar, France between 1972 and 2004 and four days per decade in Geisenheim, Germany between 1955 and 2004. This earlier wine-grape ripening is driven by climatic warming and drying, combined with management practices.

In southern Victoria, dairy silage harvesting traditionally started on Melbourne Cup Day – the first Tuesday in November. Many contractors are now starting cutting as early as August, due to a combination of warmer and drier conditions. Our recent modelling supports this by illustrating that observed patterns of pasture growth in southern Victoria have changed.

Research published in 2009 predicted an earlier onset of the drier summer in southern Australia. The growing season would be reduced by up to three weeks in late spring, but this was potentially compensated for by an increase in winter pasture growth due to warmer temperatures by 2050.

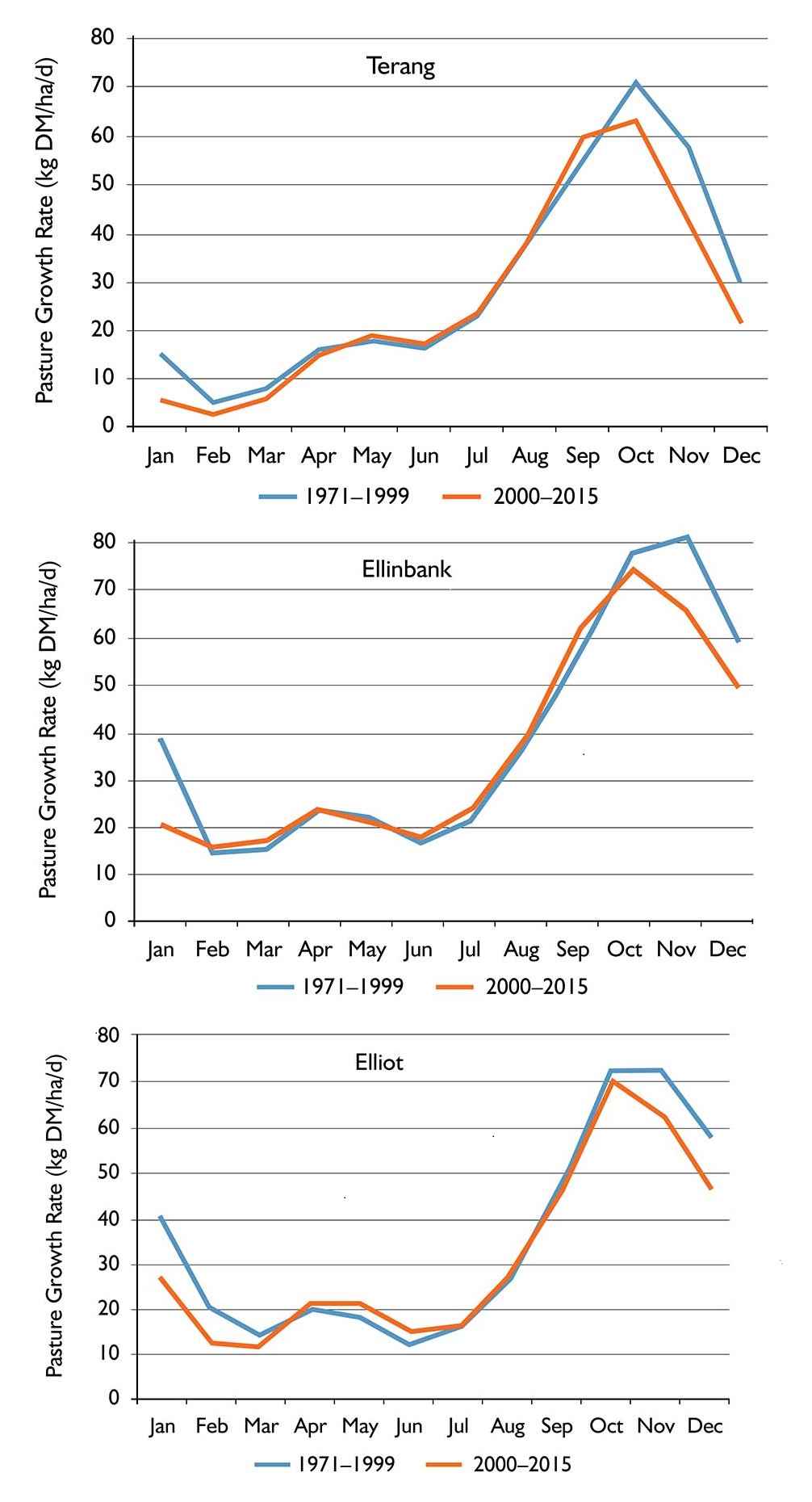

Re-running the same simulations and sites in 2015, but presenting pasture growth over the past 15 years separately from the 1971 to 1999 baseline (Figure 1), the past 15 years of pasture growth show a pattern closer to what was originally predicted for 2030 and 2050. The pastures are telling us that climate change is advancing faster than predicted in 2009.

Above: Average pasture growth rates between 1971 and 1999 (baseline) compared to 2000 to 2015: Terang in western Victoria, Ellinbank in South Gippsland and Elliott in north-west Tasmania.

The science tells us that climate change will initially result in more intense frosts across southern Australia, due to reduced rainfall leading to more clear winter skies and associated night-time heat loss. So what do the crops tell us?

Record recent frost losses in the cropping industries have prompted a national research review commissioned by the Grains Research and Development Corporation. The 2016 season delivered a series of frost events that devastated some crops, particularly in Western Australia, in what

had promised to be a record-breaking year.

The climate change sting in the tail is that warmer average temperatures also increase the rate of crop development bringing crops to the susceptible, post heading stages earlier when there are periods of higher frost risk. Estimates of damage, mainly in wheat and barley crops, range from losses of 1.5 to 4 million tonnes across Australia.

These are only a few of the growing number of climate change stories as told by plants. Other well-documented examples include coral bleaching, mangrove die-off, reduced ripening in fruit tree orchards and the rise of European wasps.

The mounting evidence from the plant and animal kingdoms over the past 15 to 20 years means climate change is not the future – it is now, we are in the midst of it.

While we can clearly cope with the trends already being experienced – through the proactive adoption of current best management practices – the extreme events along the way are the biggest challenge for farmers and land managers.

Given that we now know what extreme events are likely, we need to start working with land managers to develop appropriate risk management plans, as each region and management system will need to consider a different suite of options to manage their emerging risks.

Professor Richard Eckard is the Director of the Primary Industries Climate Challenges Centre.